Sharing the load: Conversations on equal parenting

Expert help and advice

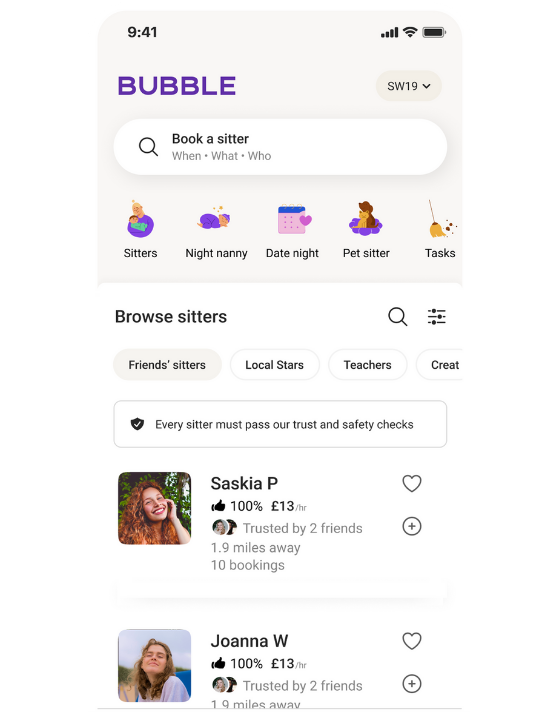

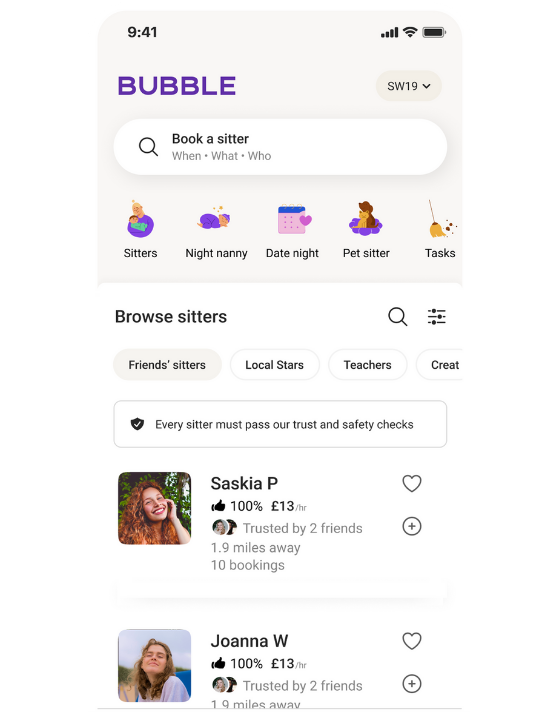

Find great childcare

Download the Bubble app to find and book childcare in as little as 30 minutes.

Download the Bubble app

Find great childcare

Download the Bubble app to find and book childcare in as little as 30 minutes.

Download the Bubble app